Controlling Essential Tremor: Brad's Story

12.07.2015

Brad Ackerman has lived most of his life with essential tremor. This common movement disorder most often affects the muscles in the head, tongue, jaw, voice, and legs. The involuntary shaking or trembling caused by essential tremor can make the activities of daily life quite difficult and in Ackerman's case, his essential tremor disrupted the movement of his hands.

Essential tremor, whose origin is not completely understood, is one of the most common movement disorders: A study published in the journal Tremor in 2014 estimated that 7 million Americans have been diagnosed with essential tremor. That’s 2.2% of the U.S. population, far greater than the 0.15-0.3% of the population with Parkinson's disease.

In many cases, essential tremor is genetic and appears in families from generation to generation. Studies show that children have a 50% chance of inheriting the disorder from a parent. In Ackerman's family, two uncles and several cousins had essential tremor. Because the condition was so visible in his family, he thought the difficulties he began to experience in childhood were normal. He learned how to compensate early for difficulties he thought were normal. "It's just who you are," he said. He learned to hold his knife, fork, and spoon in a way that allowed him to get food into his mouth without spilling. With heavier objects, he figured out how to grab them with one hand and then transfer them to the other before the tremor in that first hand would loosen it from his grasp.

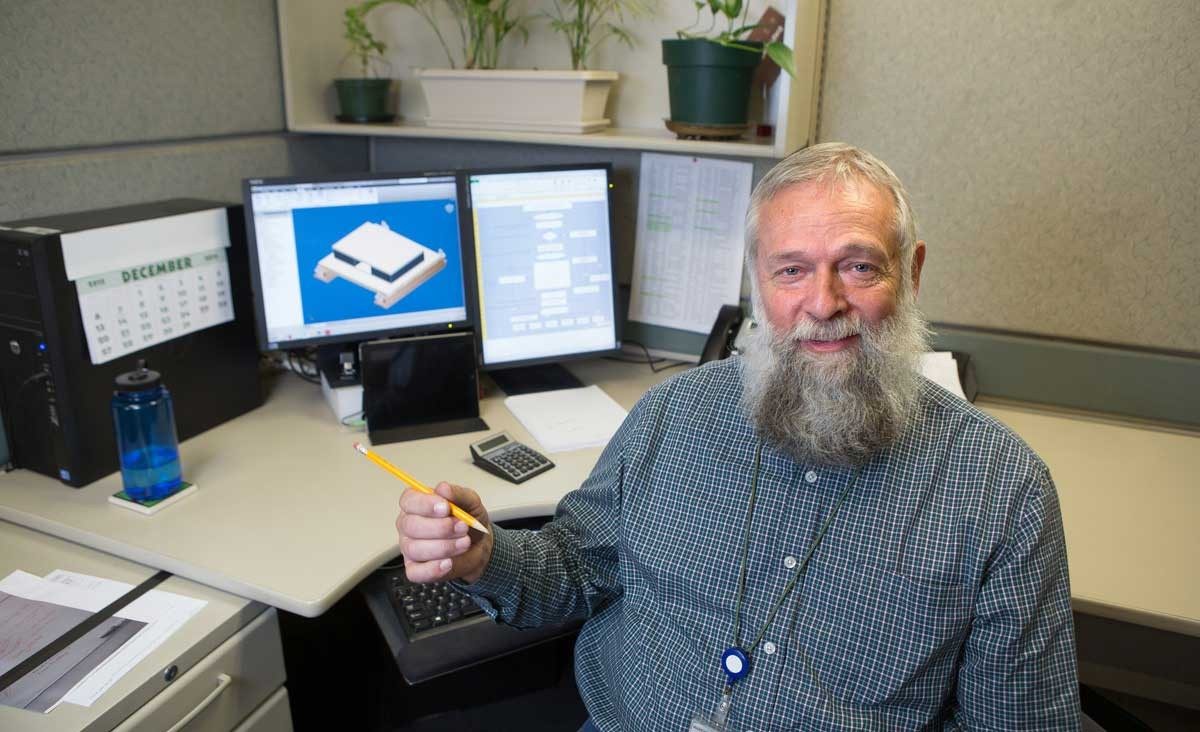

The tremor began to affect the direction of his life in other ways too. In high school, he loved drawing and painting, but his tremor meant he could not easily hold or control a pencil or ink pen to draw or a paintbrush for watercolor painting. In a form of denial, Ackerman told himself he just didn't have the talent for art. But he did reimagine how to apply his creative drive. He became an industrial designer, where he could express and execute his visual ideas with the help of a computer. If someone had a question, he could make a quick sketch that wouldn't have to be too detailed. "No one wants to think about being disabled because of something like this," Ackerman said. "It's just not something you let yourself think about."

The tremor, however, affected his social life. "I had to really think about what I would eat when I went out," he said. "What could I get into my mouth?" Adjusting his movements to maintain his typical life became more and more stressful—and stress can worsen essential tremor symptoms. His wife, Carol, knew about the tremor years before their marriage and remembers the stress she felt (and knew he must be feeling) as he struggled to light candles at their wedding ceremony, in front of their 500 wedding guests. She had also watched his condition grow worse over time. "I would notice when he would sign his name that it was illegible," she said. "It was getting worse and worse."

Doctors know what triggers it— irregular electrical activity in deep circuits of the brain, but for many years, medication was the only option available to quiet that activity. But medication doesn't work for many people. For others, medication works but produces side effects that interfere with daily life. Ackerman did not like how he felt while medicated. "It just made me want to sit and do nothing," he said. Nor did the medication keep up with the severity of his tremor. "It got harder and harder to do a drawing at work," he said. "After a while, I couldn't do it." With his livelihood threatened, Ackerman turned to a newer treatment: surgery.

Stanford Health Care neurologists and neurosurgeons have a great deal of experience with devices implanted in the brain to control its activity. The treatment is called deep brain stimulation or DBS. It's a procedure that is currently being used by Stanford Health Care doctors to treat several movement disorder conditions and psychiatric diseases.

Ackerman wasn't afraid of having surgery. He wanted to be able to do his job well and to do things that he'd never been able to do well with the tremor, including drawing and painting. "There were years of data on this procedure," he said. "I went on YouTube to watch some videos of Stanford Health Care surgeons treating patients with similar conditions."

He came to Stanford Health Care because he knew of its reputation for experience and expertise with deep brain stimulation. Neurosurgeon Casey Halpern, MD, specializes in the treatment of movement disorders with DBS. Halpern completed a fellowship in stereotactic and functional neurosurgery, with a particular focus on minimally invasive surgical techniques and deep brain stimulation.

Ackerman had his surgery in February 2014. He had to go off his current essential tremor medications before the procedure. "That allowed the true extent of the tremors to emerge," Carol Ackerman said. "It showed—a lot."

The DBS treatment Ackerman received involves MRI-guided placement of a small, insulated wire into one of the targeted brain structures. At the tip of that wire are four small electrodes that can release electrical impulses to block tremor. The wires are connected to a 2-inch by 3-inch battery pack that sits under the skin in the chest, just as cardiac pacemakers do. Like most people receiving DBS, Ackerman was awake during the procedure, talking with Halpern and the rest of the care team. Ackerman and Halpern worked together to adjust the pacemaker to address Ackerman's tremor and particular needs.

Studies that followed essential tremor patients for five years after their DBS procedure have shown a 75% percent improvement in the degree of their tremor on a standard scale that measures tremors as people do various activities.

As soon as the device was turned on and adjusted, Ackerman began to see an immediate change. "It was much better," he said, "and I can do my job better." He is much calmer, he admits. "I had such anxiety as a result of the tremor, from all the things I had to think about to get what most people consider simple tasks done. My whole life has changed. And the surgery has been so successful."

Ackerman will continue his care at the new Stanford Neuroscience Health Center, a facility that will make it easy for him to see Halpern and receive any other treatment he might need, all in the same building. It's one less stressor that will help him maintain his new freedom from the worry of essential tremor.

In January, the new Stanford Neuroscience Health Center will welcome its first patients. This five-story, 92,000-square-foot building includes advanced imaging, patient care technology and interiors designed to be sensitive to the needs of people with neurological conditions. Halpren will be one of more than 200 expert doctors covering 21 neurological subspecialties providing care for patients at the new Center.