Doctor Stories

Results from the Stanford-led Donor Heart Study Pave the Way for Increased Donor Heart Acceptance Rates

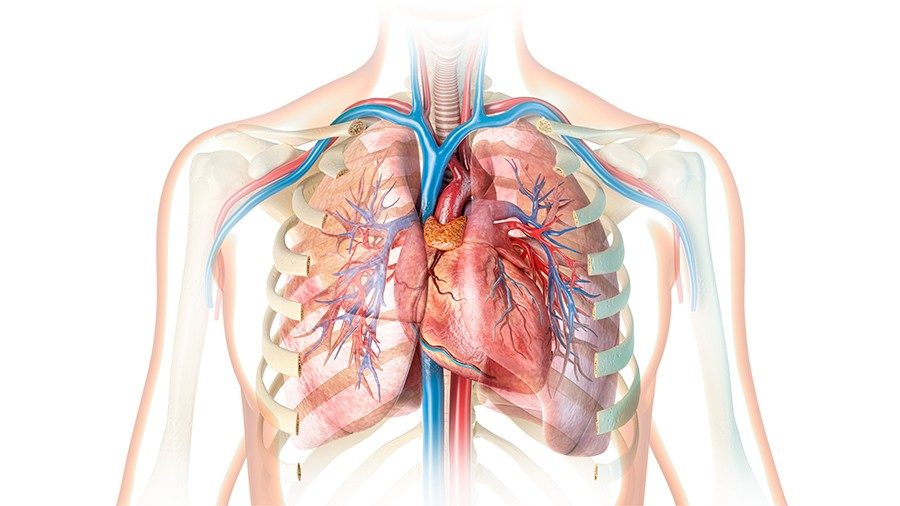

Despite consistent increases in both the number of people awaiting transplants and the number of donor hearts available since 2011,1 approximately 65% of eligible donor hearts continue to be discarded annually. This translates to extended wait times and elevated waitlist mortality.

In 2015, the National Institutes of Health funded a 5-year prospective, multisite, observational study of donor management, evaluation, and acceptance for heart transplantation to determine the underlying causes of these discrepancies. The Donor Heart Study (DHS), led by Stanford Medicine cardiologist Kiran Kaur Khush, MD, MAS, professor of cardiovascular medicine, represents the largest of its kind on donor heart acceptance.

“My hope is that these findings help establish guidelines for donor selection that translate to higher acceptance rates,” says Khush. “This can greatly expand the donor pool to more effectively meet the needs of the growing number of patients on waiting lists.”

CARE AT STANFORD

We’re recognized worldwide as leaders in heart failure care and heart transplantation, achieving excellent outcomes with shorter-than-expected wait times.

650-723-5468

Establishing criteria for what makes a donor heart acceptable

Explanations for the low rates of donor heart utilization tend to focus on surgeons and transplant centers wanting to maximize the probability of success on behalf of the recipient. Although accurate, a more nuanced analysis revealed variability in acceptance across transplant centers and even individual clinicians.

“When a donor heart is made available, the surgeon or cardiologist evaluates the offer and makes the final determination on whether the organ is acceptable,” Khush explains. In the absence of standards defining what constitutes an acceptable donor heart, clinicians rely largely on experience and limited data primarily from small case studies.

Decisions can also be influenced by the size of the transplant center and how that affects metrics on survival outcomes. “Because transplant centers are still mainly judged according to one-year post-transplant survival, smaller centers tend to be more conservative in their acceptance of donor hearts,” says Khush. This is reinforced by the significantly higher donor heart utilization rates in Europe (68% vs. 32%), where similar metrics are not used.

The DHS was a large-scale study designed to provide evidence-based guidelines to inform the decision-making process in ways that could immediately increase the number of lifesaving transplants. “We wanted to generate data addressing conditions that frequently result in non-use of donor hearts,” says Khush. “By providing evidence that these hearts are actually suitable for transplantation, we can increase the donor pool and offer patients waiting for a transplant a new lease on life.”

Identifying the incidence and impact of a common, but disqualifying condition

Left ventricular (LV) dysfunction is among the most common reasons for donor heart nonacceptance. Dysfunction in this context is defined as an LV ejection fraction of <50%. In settings involving donations after neurological death (DND), LV dysfunction frequently occurs secondary to other physiological responses following brain death.

Despite evidence of the often temporary and reversible aspects of LV dysfunction under these circumstances, its recognition frequently resulted in the heart being deemed unsuitable for transplant.

The first paper from the DHS addressed three critical questions related to donor hearts in DND settings:

- What is the incidence of LV dysfunction?

- When it occurs, how often does it demonstrate reversibility within 24 hours?

- In cases where the heart was used for transplantation, what was the effect of LV dysfunction on transplant outcome?

The study included 4,333 potential heart donors with DND status. Diagnosis of LV dysfunction was determined by echocardiogram following declaration of brain death. In the event of a positive diagnosis, a second echocardiogram was performed after 24 hours to determine changes in LV function. LV dysfunction was deemed reversible if the second echocardiogram reported an ejection fraction >50%.

The results showed the following:

- There was a 13% incidence of LV dysfunction.

- Among those diagnosed with LV dysfunction, 58% demonstrated reversibility of the condition after 24 hours.

- Among donor hearts accepted for transplant, the one-year survival rate was similar for recipients receiving a heart demonstrating normal LV function (91.3%), reversible LV dysfunction (90.1%), and nonreversible LV dysfunction (91.3%).

“The findings demonstrated not only the relative frequency of LV dysfunction following brain death, but also that it’s largely reversible,” explains Khush.

Importantly, Khush emphasizes that the similarities in survival rates between recipients suggests that many of these hearts are perfectly acceptable for transplant. “My hope is that this data reassures both clinicians and transplant centers of the safety in using donor hearts with LV dysfunction.”

Capitalizing on data from a groundbreaking study

Despite the significant challenges associated with donor-based studies of this kind, the knowledge gained and potential benefits are priceless. This is the first of many research manuscripts currently in development using the DHS data.

“We’re in the process of determining the feasibility of different predictive models of donor heart suitability and transplant success,” says Khush. “We are trying to gain a more nuanced understanding of why hearts are not used for transplant. Given enough information on the donor and the potential recipient, can we predict the outcomes after a transplant? These are some of the possibilities introduced by the DHS.”

Ultimately, the more immediate impact is simply to decrease wait times for those needing a heart transplant. “Given the national shortage of organs for transplantation, we have a responsibility to improve the process of donor heart selection and maximize their availability in a safe manner.”

Learn more about the Donor Heart Study and Stanford Health Care’s Heart Transplant Program and Advanced Heart Failure Program.

About Stanford Health Care

Stanford Health Care seeks to heal humanity through science and compassion, one patient at a time, through its commitment to care, educate and discover. Stanford Health Care delivers clinical innovation across its inpatient services, specialty health centers, physician offices, virtual care offerings and health plan programs.

Stanford Health Care is part of Stanford Medicine, a leading academic health system that includes the Stanford University School of Medicine, Stanford Health Care, and Stanford Children’s Health, with Lucile Packard Children's Hospital. Stanford Medicine is renowned for breakthroughs in treating cancer, heart disease, brain disorders and surgical and medical conditions. For more information, visit: www.stanfordhealthcare.org.